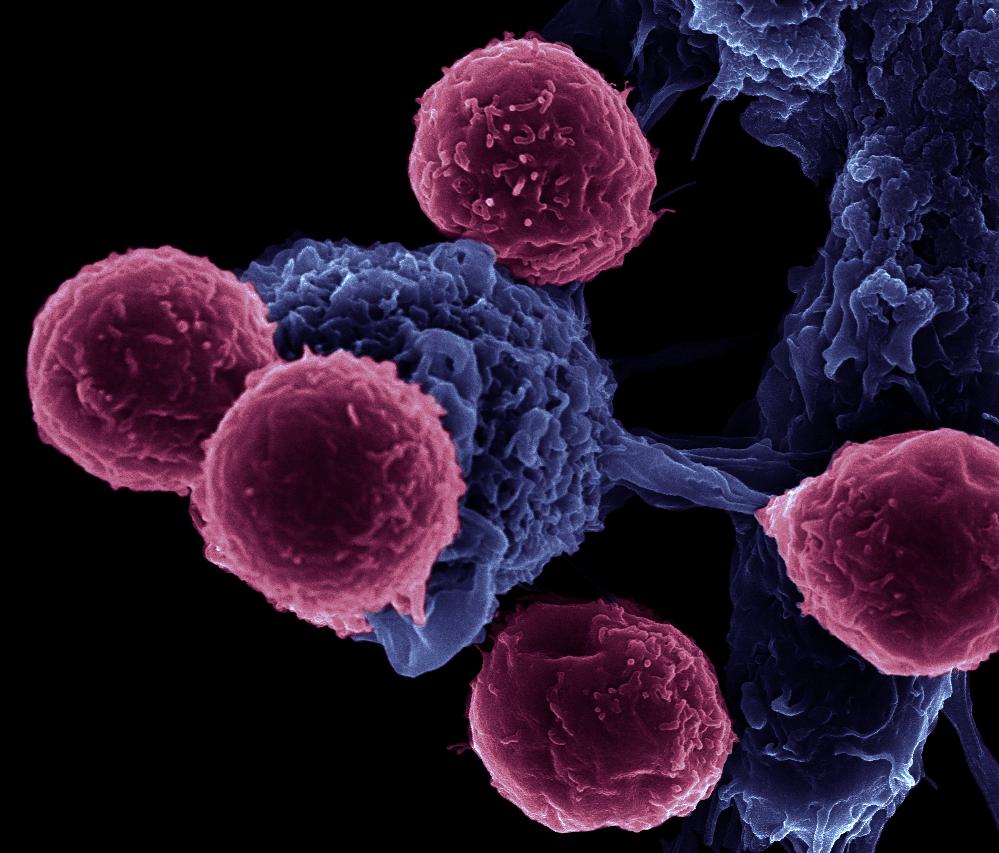

Immune system cells, otherwise known as macrophages, are designed to fight off any invading pathogens in order to protect the body. However, a new study suggests that these cells help electricity flow between muscle cells to keep the heart beating as it should. While the heart’s muscle cells contract in response to electrical signals macrophages stays squeezed in between helping the heart receive signals and stick to the right rhythm.

Up until now, researchers knew very little about the particular function of macrophages, and it was by accident that cell biologist Matthias Nahrendorf stumbled upon this find. Intrigued at how macrophages impact the heart he set out to perform an MRI scan on a mouse that had been genetically engineered not to have the immune cells. The problem was however that the mouse’s heartbeat was too slow and irregular to get a sufficient scan. The symptoms the mice had to suggest there were problems with their atrioventricular node.

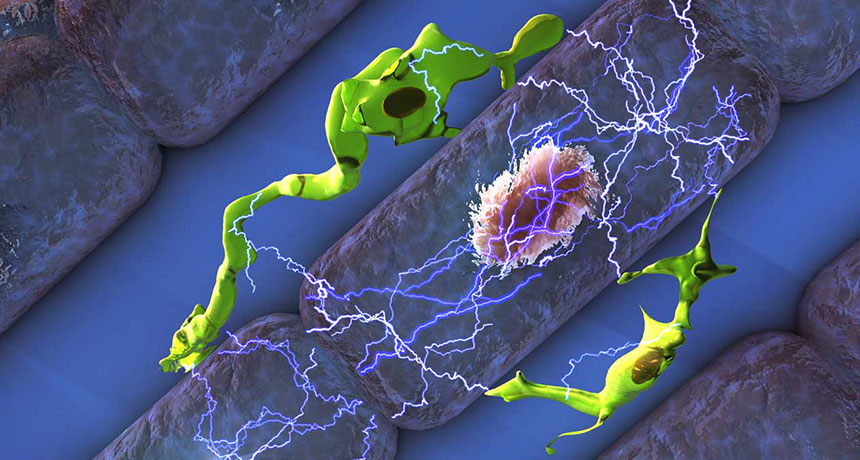

On the flip side, researchers discovered that in healthy mice, concentrated amounts of macrophages were found in the AV node. But, scientists were still no further forward in isolating a heart macrophage and testing it for electrical activity. When the researchers paired a macrophage with a cardiomyocyte, the two began to communicate through electric signals. When cardiomyocytes are in the resting state, there are fewer positive ions inside the cell than outside, but as soon as an electrical signal is received that distribution flips causing the cell to contract and transmit the signal on to the next cardiomyocytes.

Previously scientists were under the impression that cardiomyocytes were capable of this shift on their own, but have since discovered that macrophages do in fact play a vital role in that process. Through the use of protein, the macrophage links up with a cardiomyocyte allowing a transfer of its positive charges to give the cardiomyocytes a boost. Nahrendorf commented, “With the help of the macrophages, the conduction system becomes more reliable, and it is able to conduct faster.” Moving forward Nahrendorf and colleagues now need to find out if the role of these immune cells is the same in humans and whether or not they could be responsible for certain heart conditions such as arrhythmia.

More News to Read