Around 2 million Americans are affected by traumatic brain injuries each and every year. Traumatic brain injuries cause inflammation and cell death within the brain and those suffering from a head injury quite often experience lifelong memory loss, and even epilepsy. However, a group of researchers from the University of California has developed a new kind of cell therapy that gives hope to these patients.

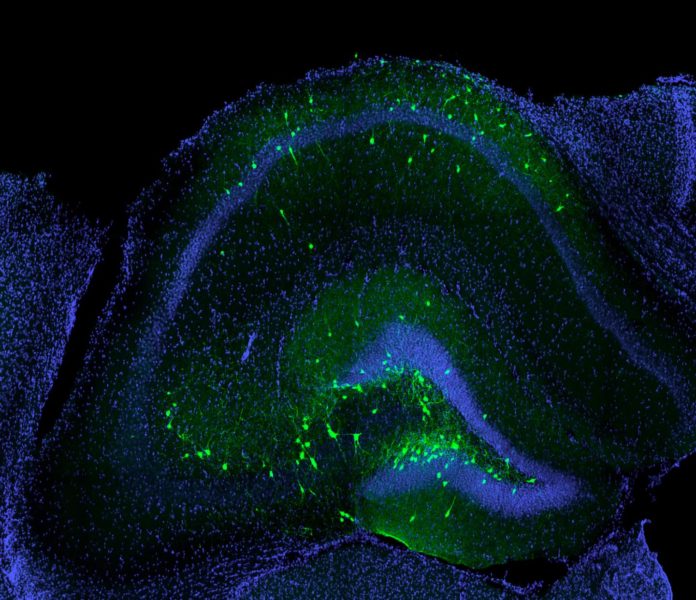

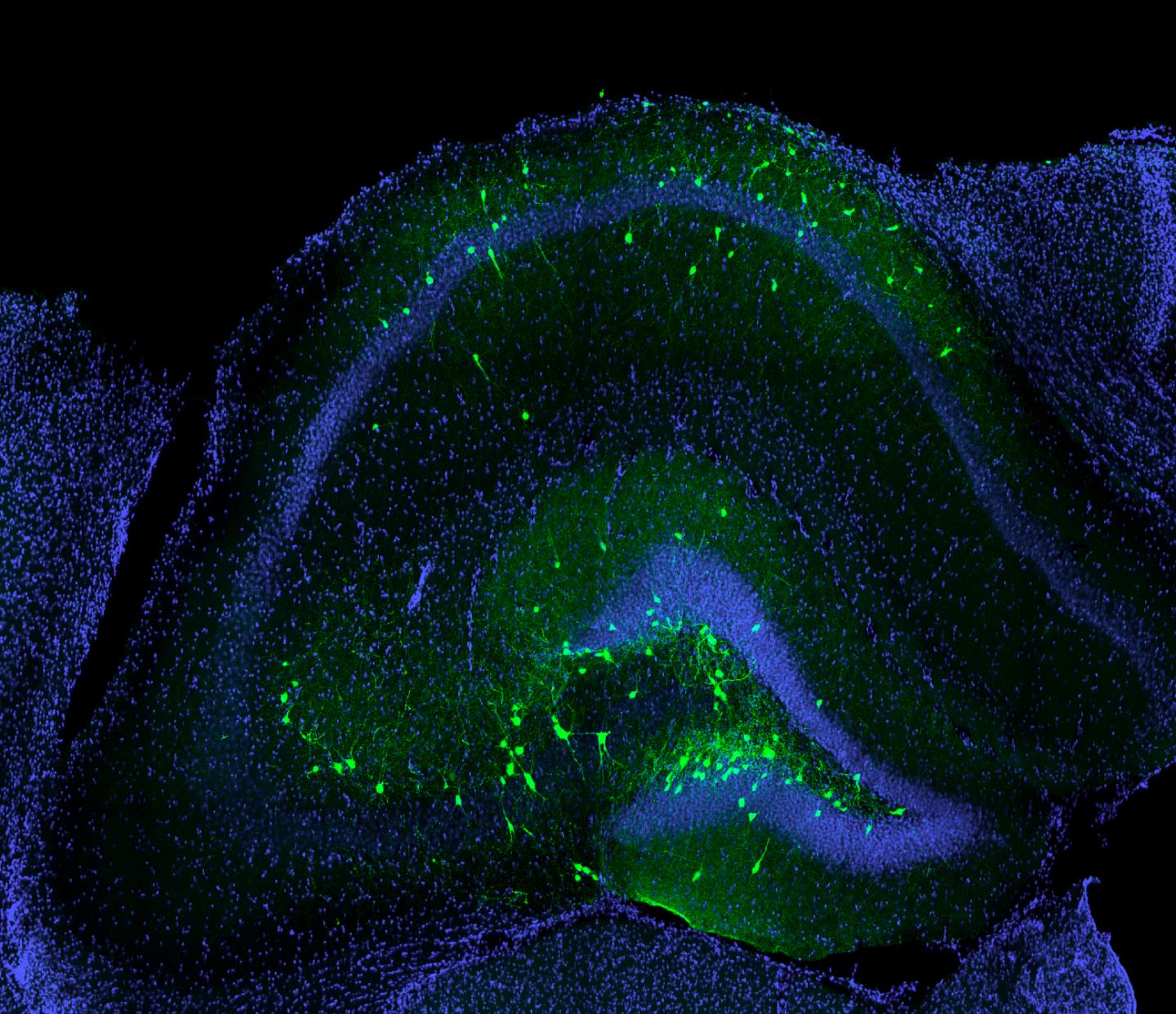

In the study, published in Nature Communications earlier this month, the UCI team explains how it successfully transplanted embryonic progenitor cells into the brains of mice with traumatic brain injury. What the researchers discovered is the transplanted neurons moved to the injury where new connections were formed with those brain cells that were injured.

Within just one month, they saw promising results. Not only were the mice showing signs of improved memory, but the cell transplants also stopped the mice from developing epilepsy. This was quite a significant result as more than half the mice that weren’t treated with new interneurons did develop the disease.

While inhibitory neurons are involved in many aspects of memory, that are highly susceptible to dying after a brain injury. “While we cannot stop interneurons from dying, it was exciting to find that we can replace them and rebuild their circuits,” said Robert Hunt, Ph.D., lead author of the study and assistant professor of anatomy and neurobiology at UCI School of Medicine.

In 2018, Hunt and his colleagues used a similar approach to restore memory in mice. However, back then the therapy was used to improve the memory of newborn mice born with a genetic disorder. But this new study was a huge leap for the researchers. “The idea to regrow neurons that die off after a brain injury is something that neuroscientists have been trying to do for a long time,” said Hunt.

To test their observations even further, the team used a drug in which to silence the transplanted neurons. “It was exciting to see the animal’s memory problems come back after we silenced the transplanted cells because it showed that the new neurons really were the reason for the memory improvement,” said junior specialist and first author of the study, Bingyao Zhu.

If this same treatment used in mice can be applied to humans, it could make a huge difference in the quality of life for those individuals. Next on the horizon is to create interneurons using human stem cells.