A new study carried out by researchers at Stanford University School of Medicine suggests that a magnetic wire could be used to capture hard to reach and scarce tumor cells as a way of detecting cancer early on. So far the technique has only been used in pigs, but the researchers are hopeful it’s a procedure that could soon be used in humans too.

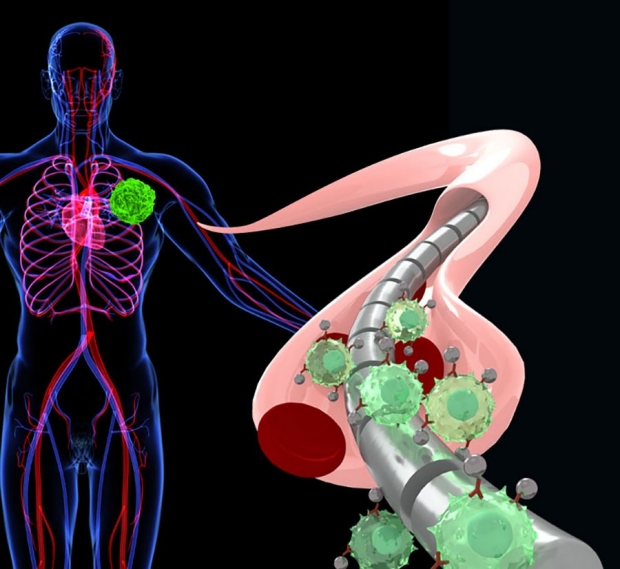

The wire is capable of attracting special magnetic nanoparticles that are likely to be inside the bloodstream if there is a tumor hiding somewhere. It’s threaded into a vein and lures the magnetized cells out very easily. This technique has proved to be more successful than any other current blood-based cancer-detection method in that it can attract up to 80 times more tumor cells.

“It could be useful in any other disease in which there are cells or molecules of interest in the blood,” says Sanjiv Gambhir, MD, Ph.D., main developer of the wire and professor and chair of radiology and director of the Canary Center at Stanford for Cancer Early Detection. “For example, let’s say you’re checking for a bacterial infection, circulating tumor DNA or rare cells that are responsible for inflammation – in any of these scenarios, the wire and nanoparticles help to enrich the signal, and therefore detect the disease or infection.”

Some cells break away from the tumor and move the bloodstream freely. These cells are known as circulating tumor cells and are the perfect candidate to be used as cancer biomarkers used in the early detection of the disease. Circulating tumor cells are few and far between, hence the need for a new method that can capture them. And, that’s where the wire comes in.

The tiny wire is around a couple of inches or so long and is about the same thickness as a paperclip. In order for it work the circulating tumor cells have to first be magnetized with nanoparticles. Then the nanoparticle and tumor cell become joined. Now, because the cell is magnetized, when it passes the wire it’s gets drawn in by its magnetic force and ends up stuck to the wire. The wire can then be removed, taking the potentially cancerous cells with it.

As mentioned above, Gambhir and colleagues are yet to try out the wire in humans. In order to that they need to have approval from the Food and Drug Administration. But still, they are confident it will work. The device was tested in pigs and placed in a vein located near the pig’s ear that’s very similar to that of a human arm vein. “We estimate that it would take about 80 tubes of blood to match what the wire is able to sample in 20 minutes,” says Gambhir.

The same technique could also be used to provide data on the efficiency of cancer treatments of to collect genetic information about tumors that are in hard to reach places. The wire itself could even become part of a long term treatment plan. “If we can get this thing to be really good at sucking up cancer cells, you might consider an application where you leave the wire in the longer term,” explains Gambhir. “That way it almost acts like a filter that grabs the cancer cells and prevents them from spreading to other parts of the body.”

More News to Read

- The Future of Digital Banking: AI-Driven Smart User Journeys

- Breakthrough in Electron Microscopy Sets World Record for Image Resolution

- How the Brain Understands What We See and Knows the Right Action to Take

- How the Brain Understands What We See and Knows the Right Action to Take

- Researchers Develop Synthetic T-Cells That are Almost an Exact Replica of Human T-Cells