There are various reasons why chemotherapy sometimes fails to work. One of those reasons, that’s only recently been discovered, a bacteria. A new study carried out by researchers at Weizmann Institute of Science’s Molecular Cell Biology Department in collaboration with Dr. Todd Golub and Dr. Michal Barzily-Rokini of the Broad Institute of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology demonstrates just how much more efficient a combined treatment of antibiotics and chemotherapy could be compared to just chemotherapy treatment alone.

The research also confirmed that certain bacteria contain an enzyme that inactivates a common drug used for treating some forms of cancer. This bacteria was found to be living within the tumors, and tumor cells confirmed Dr. Ravid Straussman. “Because the topic is so new, we first use different methods to prove that there were bacteria inside the tumors. Then we decided to look at the effect that these bacteria might have on chemotherapy,” explained Straussman.

As part of the study, researchers tested the bacteria found in the tumors of pancreatic cancer patients to see how sensitive the cancer cells were to the chemotherapy drug, gemcitabine. Results from the tests showed that some of those bacteria did, in fact, inhibit the drug from working. Further analyzing revealed that the bacterial genes responsible for this one called cytidine deaminase (CDD), which comes in both a long and short form. However, gemcitabine could only be deactivated by long form of the CDD gene.

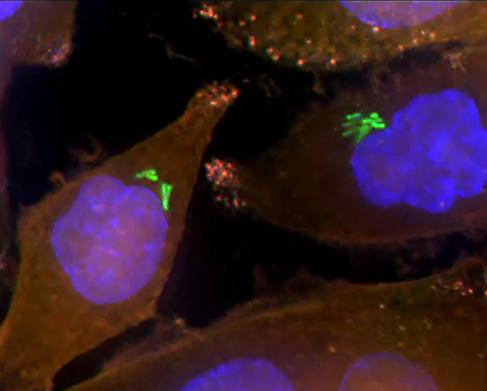

Over 100 human pancreatic tumors were examined during the study to demonstrate that these bacteria with long CDD are present in them. The group also used different methods to visualize the bacteria inside the tumors which is essential in lab studies as bacterial contamination is so common. In fact, it was a previous case of bacterial contamination that led Straussman to this research in the first place. While looking for evidence in cancer’s environment that normal cells also contribute to a resistance of chemotherapy treatment Straussman’s team found a specific example of normal cells that had made pancreatic cells resistant to gemcitabine. Trying to pinpoint the cause led the team to discover the bacteria that had accidentally contaminated the skin cells. After finding out how the bacteria degraded the drug, Straussman wondered if other bacteria have similar mechanisms for making the drug inactive and whether it too could be found in human tumors.

The new study involves more experiments in mice and focuses on cancers separated into two groups: those containing the long form of the CDD gene and those where the gene had been depleted. When the chemotherapy drug was given to the mice, only those with the CDD gene intact exhibited any resistance to it. Once combined with antibiotics this group also responded to the drug. Moving forward, Straussman now wants to know if bacteria can be found in other cancer types too and if so, what effects do they have on cancer and anti-cancer drugs and will continue his studies in this direction.

More News to Read

- Researchers Discover the Human Body’s Internal Clock

- Astronomers Detect Titanium Oxide for the First Time in Exoplanet WASP-19b

- Virtual Reality Travel Experiences That Will Blow Your Mind

- Astronomers Discover Fluctuations in Brightness of Unique Binary Star System

- Dark Energy Debate Takes Another Turn Thanks to New Supernova Analysis