Although we know both dark matter and dark energy exist, we’ve always found it difficult to prove. However, new results provided from the recent Dark Energy Survey (DES) reveals the most accurate measurements of these phenomena that we’ve ever seen. The Dark Energy Survey began in August 2013 and is a collaboration of more than 400 scientists from seven different countries.

The DES’s most recent survey unveiled the most accurate measurements we’ve ever seen when it comes to dark matter and dark energy. These measurements are very close to the original Planck measurements of the past and have enabled scientists to gain a deeper insight into how the universe evolved all those 14+ billion years ago. Scott Dodelson of Fermilab is one of the lead scientists on this project, and he is extremely pleased with the results. “This result is beyond exciting,” he says. “For the first time, we’re able to see the current structure of the universe with the same clarity that we can see its infancy, and we can follow the threads from one to the other, confirming many predictions along the way.”

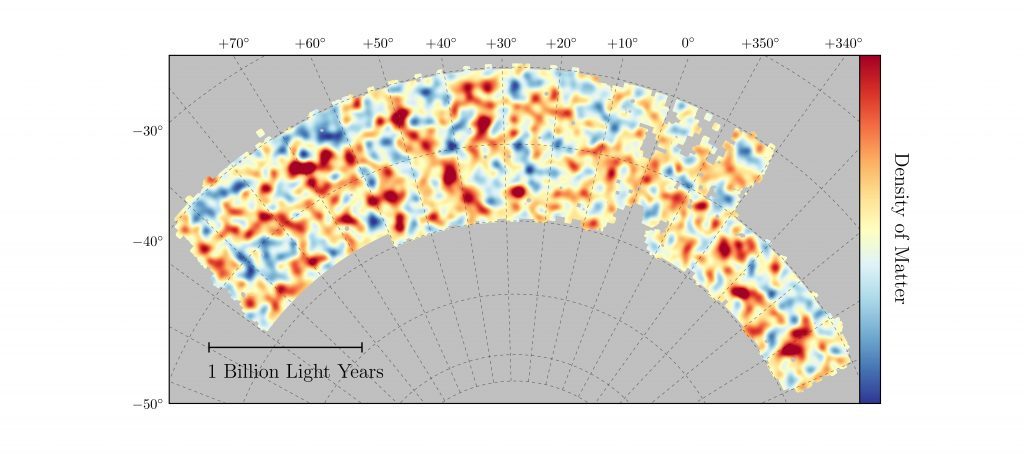

Results from the survey fully support the theory that over a quarter of the universe is made up of dark matter and that space is also filled with as much as 70 percent dark energy. It’s much easier to measure this dark energy in the distant past than today, and Planck’s map of the cosmic microwave background (CMB) radiation is a fantastic example of what the universe was like back then. Nowadays the universe is much more clumpy than it was back then. Thanks to the strong gravitational pull of dark matter mass have been clumped together over time. However, dark energy is at the other end of the scale, pushing matter apart.

Joe Zuntz of the University of Edinburgh worked on the analysis and he confirmed, “The DES measurements when compared with the Planck map, support the simplest version of the dark matter/dark energy theory.” In order to get these precise measurements, the main tool scientists used was the 570-megapixel Dark Energy Camera. It’s one of the most powerful of its kind in existence and has the ability to capture images of light from as far as eight billion light years away. Right now the camera is mounted on the National Science Foundation’s 4-meter Blanco Telescope at the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile.

The same camera is being used by the DES scientists. It will have mapped an eighth of the sky over a period of five years, with the last year of observation starting this month. The results which have just been released were from the survey’s first year in operation. “It is amazing that the team has managed to achieve such precision from only the first year of their survey,” said Nigel Sharp, National Science Foundation Program Director. “Now that their analysis techniques are developed and tested, we look forward with eager anticipation to breakthrough results as the survey continues.”

In order to accurately measure the dark matter, two methods were used. First, DES scientists created maps of the galaxy positions, and second, they measured the shapes of more than 25 million galaxies to map exactly where patterns of dark matter appeared over billions of light-years. This was done using gravitational lensing. The team also had to develop new ways in which to detect the tiny lensing distortions. To do that they created a new dark matter map that’s 10 times larger than the one released in 2015 by the DES and is set to keep growing.

Co-developer of the new method for detecting lensing distortions is Eric Sheldon, a physicist at the DOE’s Brookhaven National Laboratory and he said, “It’s an enormous team effort and the culmination of years of focused work.” So, another victory in the world of physics so it seems.

More News to Read

- Want to Learn PHP? Here are Tips and Sources to Start

- VIral and Human DNA combine to make Vaccines more Potent

- Are Twinkling Little Enzyme’s the Answer to Curing Cancer?

- New Experimental Drug Kills Cancer Cells When Combined With Chemotherapy

- Scientists Discover New Hair Growth Technique Using Stem Cells